A woman mistreated and silenced by the men in show business is a tale as old as time. So too is reinvention – the tireless process many stars go through to escape their past. It was a succession of unwise relationships that the complex one-time showgirl and silent film actress Mary Nolan (née Mariam Imogene Robertson) inadvertently detonated what should have been two transformative careers in the space of a decade.

Mary was born in the boondocks of Hickory Grove, Kentucky, in 1902. She weathered a miserable childhood, passed from a foster home to a Catholic orphanage in Missouri after her mother tragically passed away from cancer in 1908. Following the death of her sister, Sally, some years later, Mary and her brother Ray were hired out as farm labourers by their grandmother, who was ill-equipped to care for them. Eventually, their older sister, Mabel, was able to take them in.

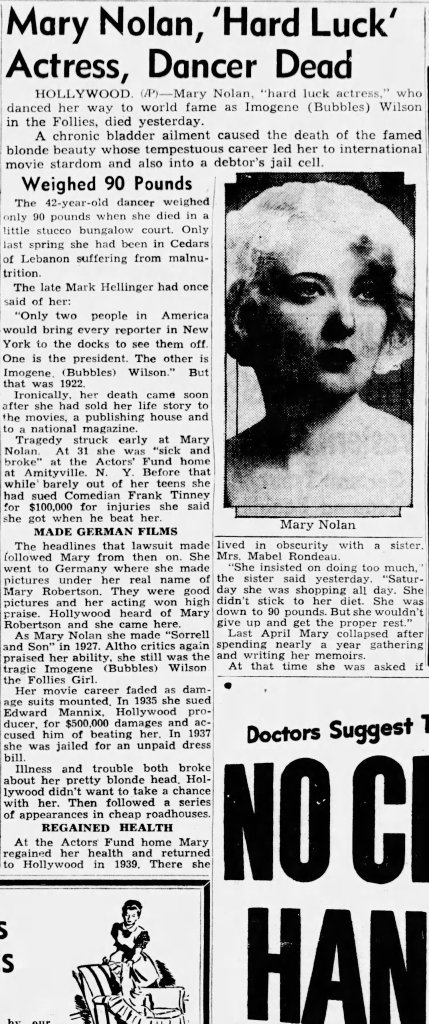

Mary travelled with Mabel to New York in 1919 and quickly found work as a teenage artists’ model, posing nude for the likes of James Montgomery Flagg, Arthur William Brown and Charles Dana Gibson. She was a fragile beauty with ice blonde hair, a curiously wan complexion and perennially sad China blue eyes that spoke of one accustomed to sorrow. Before long, she attracted the attention of Florenz Ziegfeld and began performing in the Ziegfeld Follies under the moniker Imogene ‘Bubbles’ Wilson – one of various identities she would adopt throughout her career. She was so popular that she was voted the most beautiful of the Ziegfeld girls of 1923, and columnist Mark Hellinger once wrote, “Only two people in America would bring every reporter in New York to the docks to see them off. One is the President. The other is Imogene “Bubbles” Wilson.” Though Mary enjoyed the glitz of the Follies, it wasn’t without its setbacks. During try-outs for her first show, she attended her first party as a Follies girl in Atlantic City alongside such stars as Tallulah Bankhead. ‘When the part broke up in the morning early hours I went to my room’, she recalled. ‘I slipped off my clothes, put on my negligee and crawled into bed […] My bedroom door opened and one of the men I had met during the evening stepped in and closed it behind him’. Though Mary escaped this ‘man who later became famous in Hollywood’, the incident remained an indication of the nefarious things to come.

However, Mary quickly became tabloid fodder following an abusive and highly publicised affair with the questionable blackface comedian, Frank Tinney. She met Frank when performing in the chorus of the Hammerstein show, Daffy Dill. Though she was successful, she was still young and inexperienced in matters of romance. Frank was the leading man and a prolific boozer who was married to former singer and dancer, Edna Davenport, with whom he fathered a son. Mary was flattered by his attentions. Later in life, she reflected, ‘I was in love with Frank Tinney, the comedian, not Frank Tinney, the man […] I, a nobody through the eyes of my own inferiority complex, was captivated by the attentions of the star of the Music Box show, the toast of Broadway’. In May 1924, Frank and Mary got into a physical altercation in her apartment after he awoke to find her with a male reporter, with whom she’d had dinner. Mary later pressed charges against her lover, telling the court, “Mr Tinney got angry. He accused me of being too friendly with the reporter.” She recounted how Frank had beaten her, knocked her to the ground and deftly kicked her, before hitting her across the head with a cigarette stand. She attempted suicide following the altercation, much to the amusement of the press who insinuated that she’d thrown a ‘suicide party’ as a publicity stunt. ‘Present at the bottling fete, as such things are so vulgarly known, was a newspaper reporter’ one columnist claimed. ‘He informed Bubbles (drawing from his store of professional knowledge), that if she were going to commit suicide, she better hurry if she wanted to catch the next morning’s editions’. Despite witness testimony and Mary’s visible injuries during the trial, the grand jury refused to indict Frank. The defence framed her as a hysterical little girl hungry for publicity.

But the pair soon reconciled. News reports whispered of Mary sporting black eyes and bruises. It was even rumoured that Frank’s excuse for this was, “My hand slipped”. Incensed by the continued negative publicity, Ziegfeld fired his star after she was pictured saying a tearful goodbye and confessing her love to her beau as he boarded the Columbus for England. She supposedly told reporters, “Frank hadn’t had a drink and was his sweet natural self. Of course, I do like notoriety, but love is too sacred to be discussed in the papers.” Edna divorced Frank and wrote a series of syndicated press articles dishing the dirt on their marriage, exposing Frank’s previous liaisons with the Titian haired Ziegfeld star, Mary MacDonald, as well as an incident in which ‘Miss Nolan’ appeared at their marital home with a knife tucked up her sleeve. Though she lay the blame solely at her manipulative ex-husband’s feet, she couldn’t resist penning a few patronising jabs in regard to Mary. ‘The child – she was scarcely more than that then – meant less than a row of rimless zeros to me’.

Mary and Frank split following his trip to Europe, and the showgirl fled to Germany to start afresh. She adopted the name ‘Imogene Robertson’ and embarked on a short-lived stint in film. She achieved success as a respected UFA star, appearing in 17 German silent films during her time in Europe. Her earnings quickly soared to approximately $1,500 a week, and she became an important figure in the illustrious Weimar era of cinema. Soon, American studios were sending her invitations to perform stateside. But the American press continued to view her with suspicion and were eager to glean scandalous tales that would reinforce the star’s bad reputation. Studio gossip began to circulate that Mary was difficult to work with, reportedly staging dramatic scenes designed to garner sympathy and potentially more money. It was also rumoured that Italian director, Antonio Frenquelli, had attacked her when she rejected his advances. He was consequently deported, leaving Mary briefly confined to a sanitorium with shattered nerves. She also found herself tangled in the first of many legal spats regarding unpaid bills and alleged theft, having reportedly stolen from her maid, Martha Ziemer, before firing her.

In 1927, she returned to the United States and signed a deal with United Artists, hoping the dust of her past liaisons had finally settled. One particularly tasteless article scoffed, ‘It wasn’t just because Miss Imogene (Bubbles) Wilson got her lovely faced punched again that she recently scurried home from Germany’. US women’s organisations voiced strong opposition to Mary’s return, and Will Hays – Hollywood’s dubious lynchpin of morality – harboured serious doubts about her suitability to the industry.

Nevertheless, she changed her name once again – this time to the sturdy ‘Mary Nolan’. She was informed that this was because her own name was too cumbersome for marquees, but Mary knew it was an effort to reinvent her public persona, and she was grateful. She received favourable reviews for her performances in box office hits including her role as the alcoholic sex worker, Maizie, in MGM’s West of Zanzibar (1928) and Desert Nights (1929), in which Variety acknowledged her improved performance. Critics lauded Mary Nolan the actress, noting her keen ability to convey pain more convincingly than any seasoned star. But sympathy for Mary Nolan the person was lacking.

After signing with Universal Pictures, Mary became entangled in yet another abusive romance. This time it was with the hot-headed MGM executive, Eddie Mannix, a known public relations mogul and ‘fixer’ with rumoured ties to the mob. He was embroiled in a few scandals throughout his career, including the cover-up of Joan Crawford’s erotic film, Velvet Lips, and the mysterious death of George Reeves. ‘He fascinated me’, Mary later recalled, ‘but he had a dual personality like most men have. One I loved. The other I hated. I endured on to hold the other’. One day, the besotted actress threatened to tell Eddie’s wife of their relationship when he attempted to end the affair. He responded by beating Mary so badly that she was hospitalised for 6 months and reportedly underwent 15 surgeries to repair the damage to her abdomen. She was briefly confined to a wheelchair but continued to shoot films, only exacerbating her condition. It was during this time that she was administered heavy doses of morphine to alleviate her constant pain, and she soon became dependant. ‘I was a dope addict, but I didn’t realise the fatal significance of those words then’, she wrote. ‘I thought dope was taken only for a thrill, that most of the addicts were poor unfortunates who didn’t know better’. Ironically, she played another sex worker in Shanghai Lady (1929) who resolves to change her life after an extended stay in an opium den.

Soon, Mary’s increased drug abuse and behaviour on set became unmanageable. Where she could previously channel her past traumas into affecting performances, the quality of her work was now diminishing. In Young Desire (1930), she portrayed a carnival dancer who tragically ends her life, believing she’s not suited to her socialite lover – another poignant role reminiscent of her erstwhile romances. Her co-star, William Janney, callously reflected, “The picture was a mess because of Mary Nolan. She took dope and practically everything else. She was supposed to have all these diseases and it scared me to death when she would stick her tongue down my throat during our love scenes and rub herself all over me. I would go to the dressing room and gargle with Listerine because I was terrified she was going to give me something’. She was fired from the production of What Men Want (1930) and replaced with Pauline Starke following an argument with the film’s director, Ernst Laemmle, reportedly over learning that she was the only actor who hadn’t received a close-up. Universal bought out the remaining time on her contract after she threatened to file a lawsuit, claiming that the studio had injured her reputation as an actress. Photoplay’s Cal York commented “That Nolan girl has torn Universal limb to limb. She’s passed fighting talk to everyone from Carl Laemmle to the boy who waters the elephants. She has demanded, raged, stormed and cause more trouble than 100 ordinary actresses”. The troubled star could only secure supporting roles in low-budget pictures for the remainder of her film career.

In March 1931, she wedded stockbroker, Wallace T. McCreary, and the couple opened Mary Nolan Gown and Hat Shop in Beverly Hills to bolster their flagging finances. Wallace had lost a reported $3 million on the Stock Exchange the week before they married. Several months later, the couple were convicted of 17 labour law violations after failing to pay wages to five employees. Mary spent 30 days in jail and filed for bankruptcy in August 1931. She divorced Wallace the following year, telling the press, “Like children, we thought money didn’t matter and married anyway […] Hollywood did not want me to be married. Everything I do is wrong. Even when I do the right thing”. She made her final film, File 133, for Allied Pictures in 1933, before relocating permanently to New York. Once again, she was dogged by accusations of theft. A five-state, all-points bulletin was issued for Mary in November 1934, regarding a £2,000 bankroll that was stolen from impresario, Louis Kessman. Mary was arrested but was released the following day when a telegram arrived at the court saying the charges had been withdrawn.

Unable to secure further work in film, Mary resorted to vaudeville appearances at the Piccadilly theatre in London and to singing in cheap roadhouses and clubs across the US. She lamented, “I don’t like nightclubs, but I have to live. I’m not a singer, but I have to make a living”. But she still dreamed of returning to the big screen. In 1935, she filed a lawsuit against her former lover Eddie Mannix, citing assault and career sabotage, and demanded $500,000 in damages. In response, Eddie enlisted the head of publicity at MGM, Howard Stickling, to leak lurid stories about the former actress’ sex life to the press. The pair even hired a private investigator, who threatened Mary with arrest for the possession of morphine after visiting her house. She was briefly jailed again in 1937 for failure to pay a $500 debt and was transferred to Bellevue Hospital to undergo psychiatric treatment – the first of numerous hospital stays incurred by ailing mental and physical health. In 1941, she sold her life story to The American Weekly, which was serialised and syndicated under the title, ‘Real Life Follies of “Bubbles” Wilson: Confessions of a Follies Girl’. In the first instalment, she deftly summarised the fate of many vulnerable women who’ve broken into show business in the opening paragraphs. ‘Some may say I’m a victim of my own folly – but I’ve always wondered why life seems to expect so much more from a beautiful woman than it does of her less-favored sisters. What life usually does is to give them so much in the beginning, fame, success, adoration, then crushes them with heartaches and tragedy’.

The renewed fascination with Mary’s life sparked conversation about writing her memoirs and turning her story into a screenplay. In the autumn of 1948, she contacted writer, Jack Preston, and asked him to work with her on her autobiography, fearing that her time was up. In the spring of the same year, Mary had been hospitalised and treated for a gallbladder ailment and malnutrition, having dropped to a frightening 80 pounds. The pair worked on her memoirs for just over two months. However, on 31 October 1948, Mary was found unresponsive from an overdose of the barbiturate sleeping pill, Seconal. She was only 45. One of the few possessions in her modest property was Rudolph Valentino’s antique grand piano, which she’d purchased in his memory. A child’s poem lay next to her body, along with a handwritten note in the margins that read, ‘If this were only true’. Her death was ruled ‘accidental or suicide’. She rests in the Abbey of Psalms mausoleum in Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Sources

- ‘Confessions of a Follies Girl’, The Atlanta Journal, 12 Oct 1941, p.19.

- Eve Golden, Golden Images: 42 Essays on Silent Film Stars.

- ‘Fair Imogene Now Has Both Eyes Colored’, The Times, 5 Oct 1924, p.1.

- ‘Glorifying the American Girl’, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 17 Jan 1926, p.2.

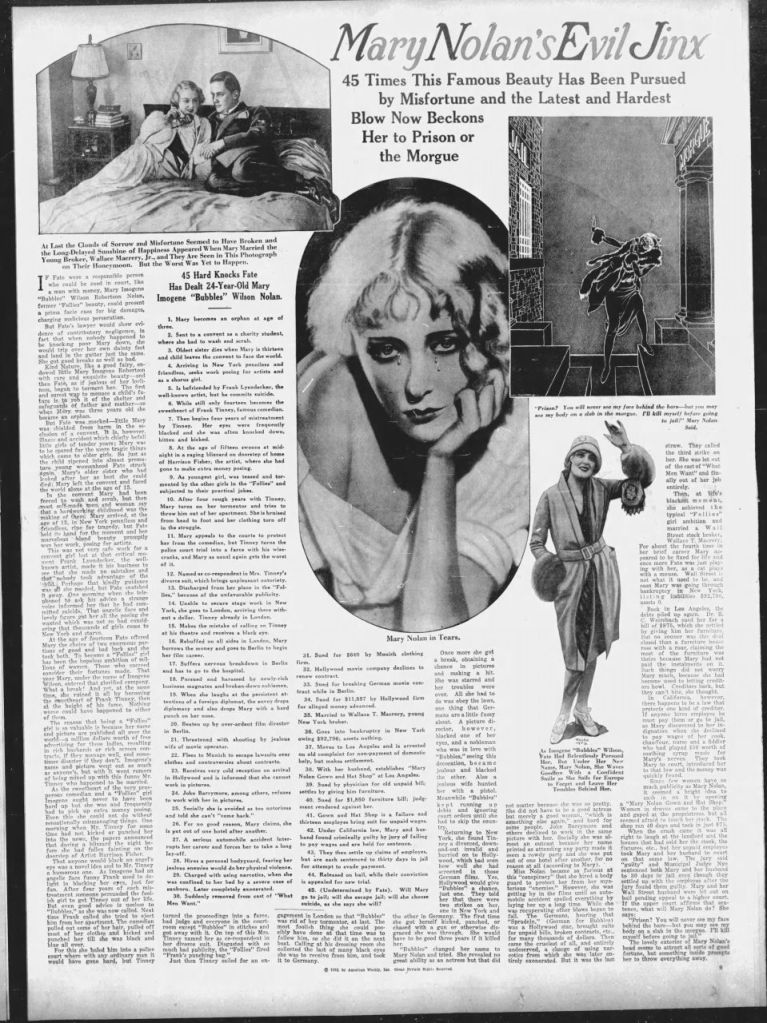

- ‘Mary Nolan’s Evil Jinx’, San Antonio Light, 3 April 1932, p. 9.

- ‘Mary Nolan, “Hard Luck” Actress, Dancer Dead, The Post-Standard, 1 November 1948, p.2.

- Michael G. Ankerich, Dangerous Curves Atop Hollywood Heels: The Lives, Careers and Misfortunes of 14 Hard-Luck Girls of the Silent Screen.

- ‘My Laughs and Tears as the Wife of Frank Kinney’, The Tulsa Tribune, 5 October 1924, p. 18.

- ‘Success and Failure, Marriage and Divorce,’ Photoplay, May 1932.

- ‘Real Life Follies of “Bubbles” Wilson’, The Atlanta Journal, 16 November 1941, pp. 64-65.

- ‘Real Life Follies of “Bubbles” Wilson’, The Tennessean, 12 October 1941, pp. 12-19.

- ‘Why Imogene Wilson Came Back From Germany’, San Antonio Light, 13 March 1927, p. 3.

Leave a comment