Pierre Molinier was a surrealist painter, photographer and object maker most noted for his exploration of fetishism and autoeroticism. He is often considered a ‘forgotten Surrealist’ and an inspiration to a succession of body artists including Catherine Opie, Hélène Delprat and Robert Mapplethorpe. Owing to his depiction of gender performance and sexual transgression, Molinier has garnered posthumous cult status as a queer iconoclast.

The artist was born on 13th April 1900 to a working-class Catholic household in Agen, France. Molinier’s mother worked as a seamstress and his father as a housepainter. Some have rumoured that Molinier’s aunt was an authoritative figure who forced her nephew to wear women’s clothing, thus shaping the fetishistic obsessions that came to dominate his work. We know for certain that Molinier was excited by women’s legs from a young age; particularly stockinged limbs arched at the feet by high heels. Reflecting on his childhood, he recalled straining to caress the legs of his mother’s employees. “It was the time of long skirts, to which weights would be sewn at the bottom to hold them in place” he recalled. “I would go underneath these seamstresses’ skirts and touch their thighs, their legs, their stockings […] I would kiss their thighs.” He was particularly enraptured by his sister Julienne, and often cited her as instrumental in his psychosexual development. “I was very much in love with my sister’s legs”, he recalled. “My sister was very attractive”. He claimed to have once been beaten by his father when he was caught in an incestuous act: kissing and fondling his sister’s thighs.

Molinier studied with the Brothers of the Christian Schools of Agen, though he alleged he was schooled by the Jesuits – one of many stories that contribute to suspicions of long-term myth-making. He began his art practice as a landscape painter working in fauvist and impressionist tradition, annually exhibiting his paintings in local Bordeaux salons. However, he expressed a distaste for convention early in his career. In 1928, he founded the Société des artistes indépendants bordelais together with several other painters, advocating for art without constraint. He moved to the L’Atelier du Grenier Saint-Pierre, 7 rue des Faussets, in 1931 – the mirrored apartment that would serve as studio and tableaux vivant until his death. He married Andrea Lafaye the same year, with whom he fathered two children.

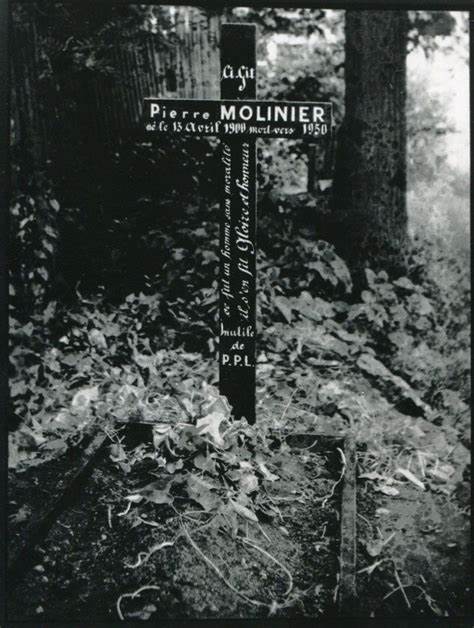

Biographers have stated that Molinier entered an esoteric society in the 1920s. Some assert this was the masons; others have refused to be so concrete. In the 1940s, the artist became increasingly inspired by esotericism and magic. Supposedly, emissaries of the Dalai Lama ordered drawings from Molinier, and it was through the reproduction of mandalas that the artist claimed to have reorientated his practice. His composition became kaleidoscopic, largely focused on androgynous bodies that converge, mutate and transform through increasingly transgressive acts. His vision was deftly summarised by the inscription on his premature grave, which he erected outside his place of work in 1950:

Here lies

Pierre MOLINIER

born on 13 April 1900 died around 1950

he was a man without morals

he was proud of it and gloried in it

No need to pray for him.

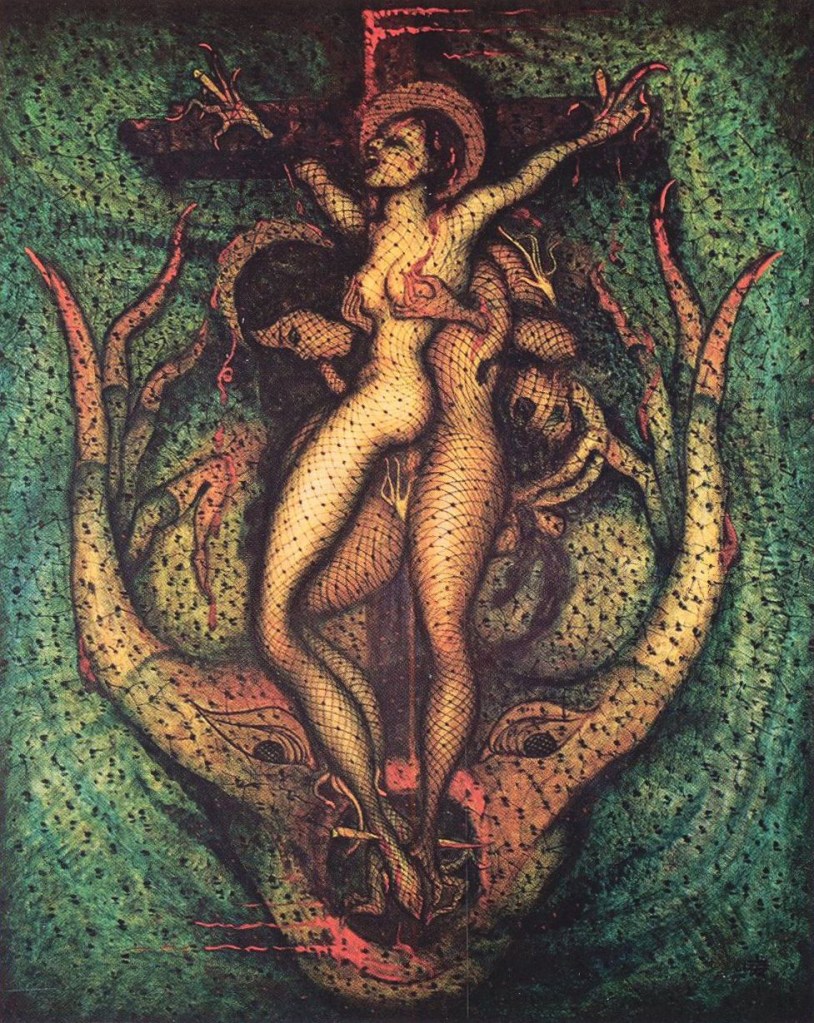

The funerary cross indicated a definitive move away from traditionalist painting to embrace the psychological through symbolism. Molinier’s experimentalism scandalised the Bordeaux Salon des Indépendants when he presented his painting Le Grand Combat in 1951, which depicted a furious tangle of limbs and breasts rendered in sullied shades of emerald, fawn and rust. Authorities ordered for the painting to be removed, but Molinier merely covered it with a black cloth on which he pinned a protest defending artists’ rights. He was subsequently thrown out of the institution. However, Molinier contacted the Surrealist artist André Breton around this time, who saw something special in Molinier’s work. In a letter to the artist, Breton was impassioned: ‘Be assured, dear Pierre Molinier, that the Surrealists are very much your friends.’ Molinier collaborated on several issues of Breton’s magazine, le surréalisme, même, and in 1956, he exhibited 18 paintings and some drawings at Breton’s Parisian gallery l’Étoile scellée. Breton kept Succube and La Comtesse Midralgar for his private collection. Breton hailed Molinier’s exhibited works as ‘deliberately magic’, gushing that the artist’s practice ‘breaks the law that says that every painted image, no matter how evocative it may be, nevertheless remains an object of conscious illusion and cannot aspire to a plane on which it makes an active intervention of life’.

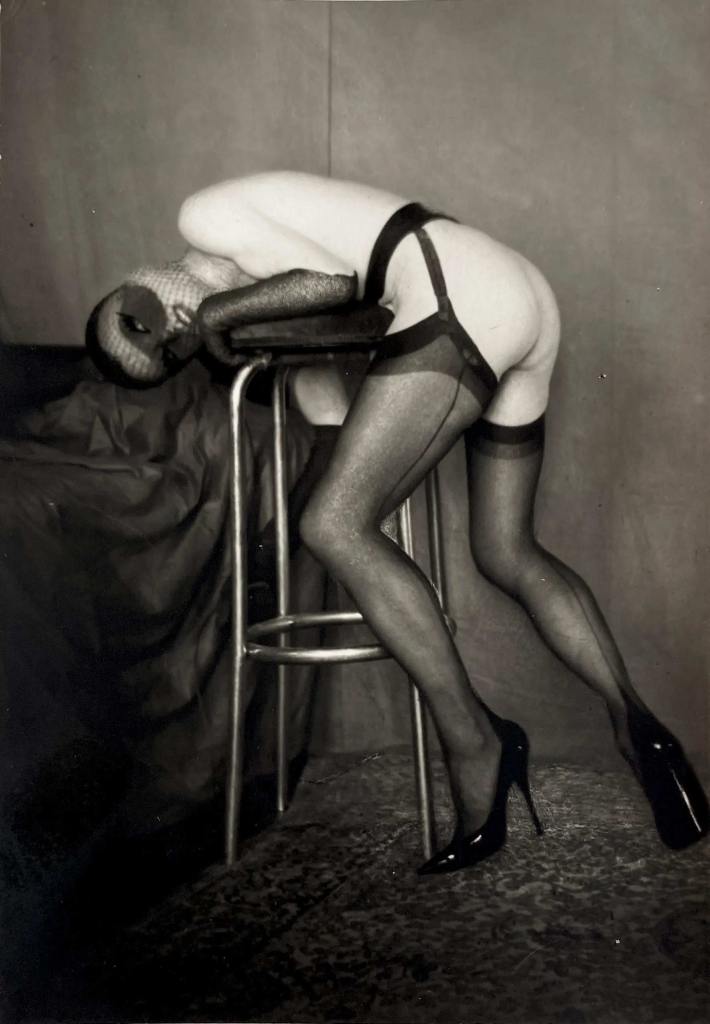

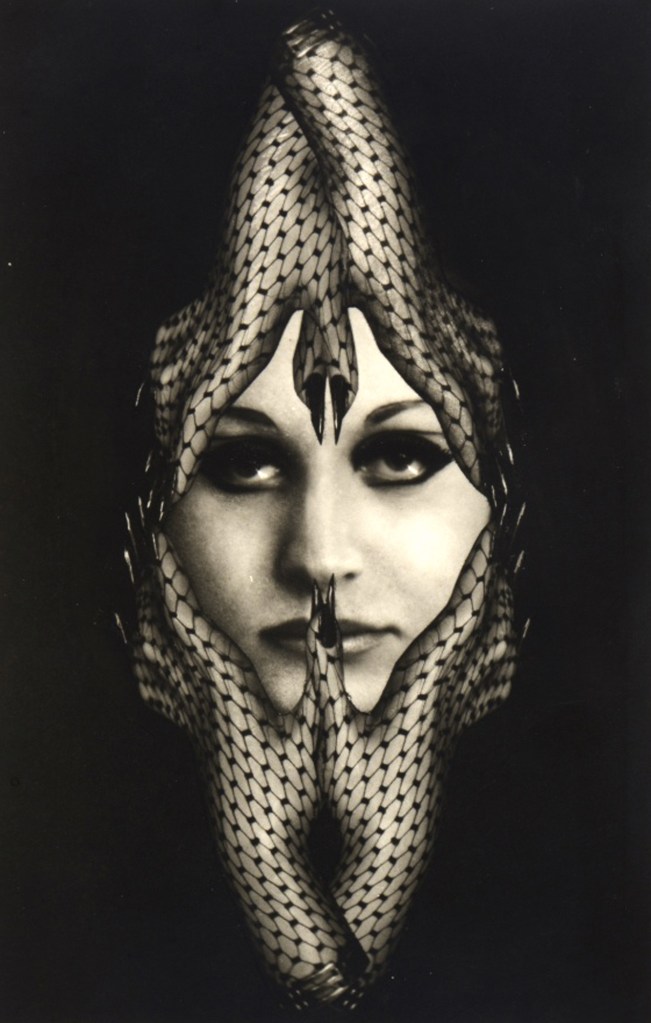

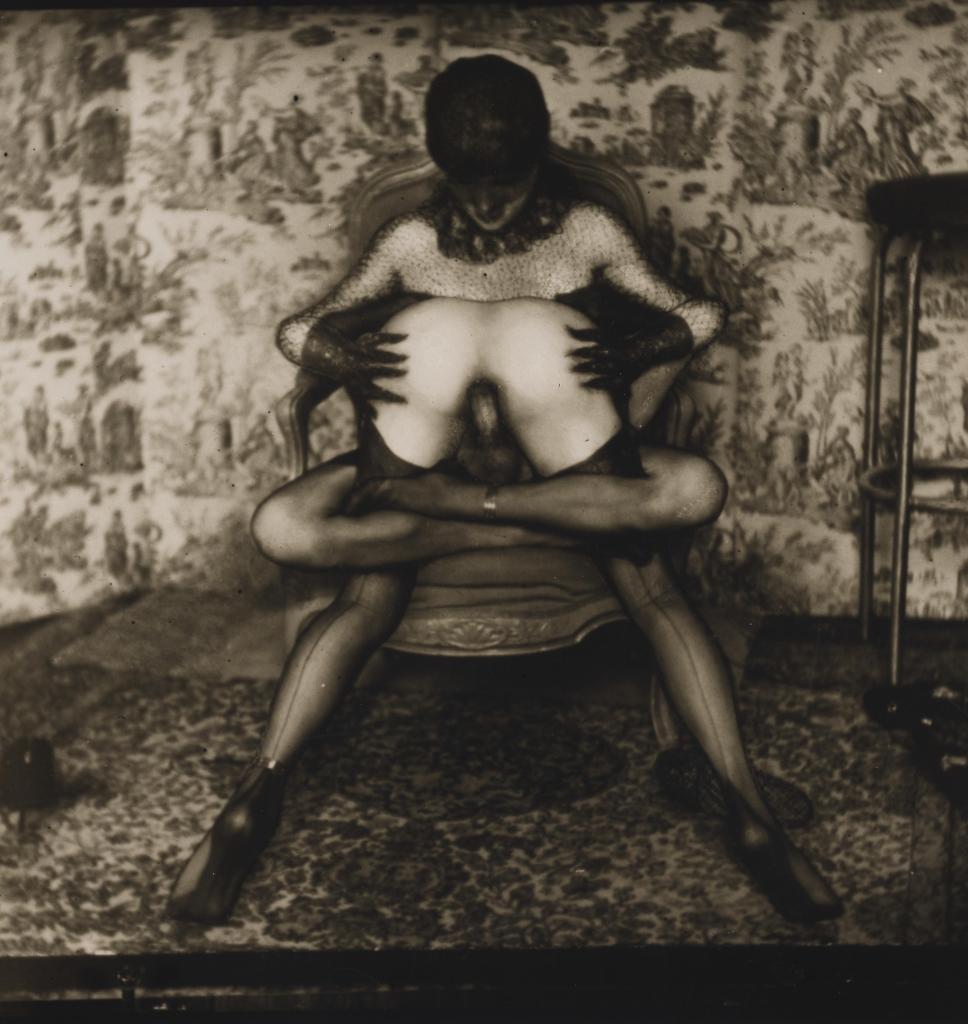

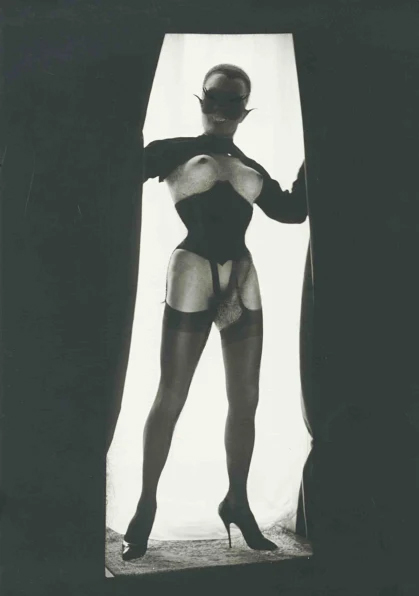

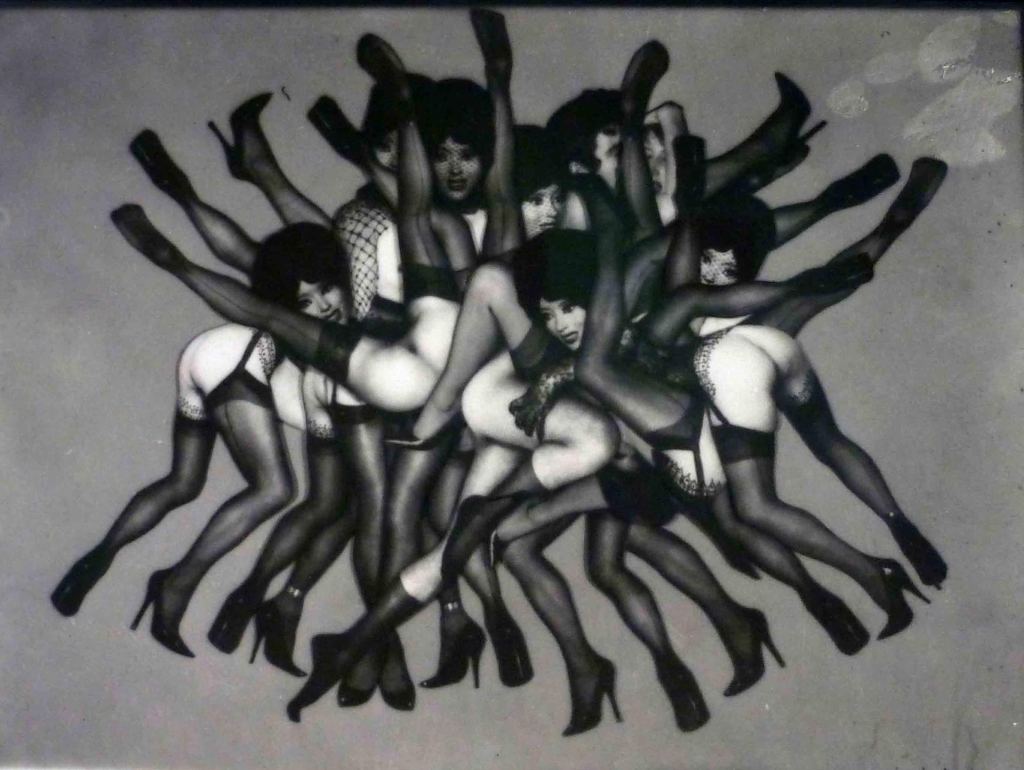

It’s around this time that Molinier began developing the corpus of photography he’s most readily associated with. He used models and mannequins to create a voluptuous ceremony of gender ambiguity and sexual deviance. Hanel Koeck – a German sadomasochist – appears in countless photomontages in fierce black eyeliner and bouffant; the very image of a 1960s femme fatale who emasculates as much as she titillates.

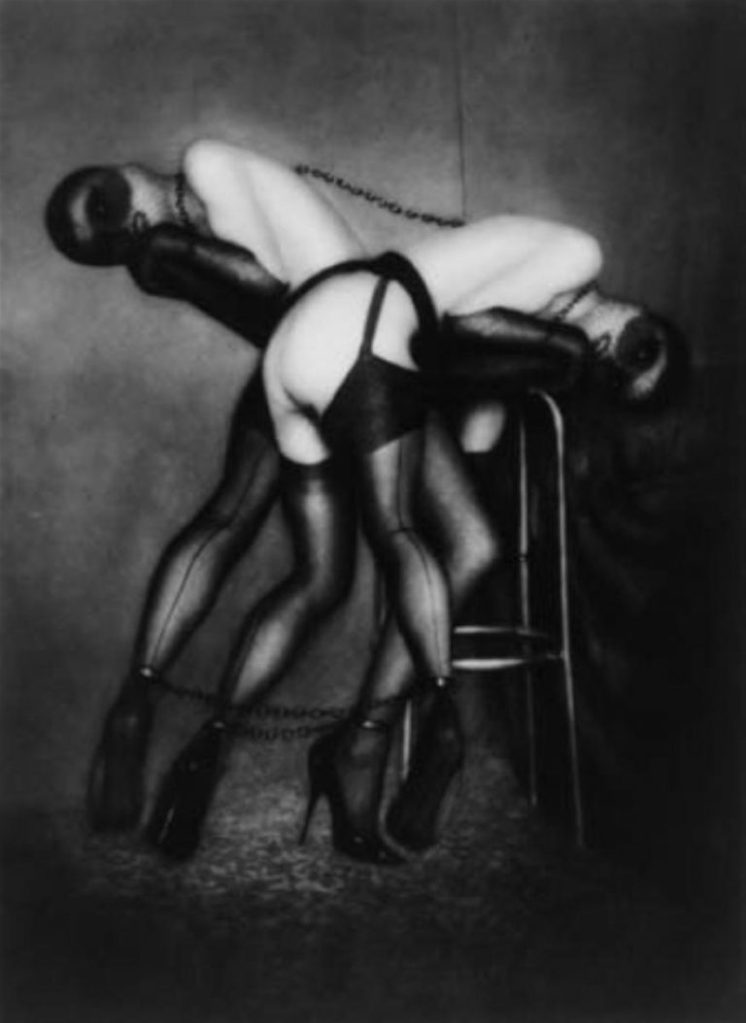

Oftentimes Molinier served as his own muse and object of desire. Some images are relatively tame – Molinier appearing as a transvestite in a fetishistic uniform of stockings, garter belt, stilettos and corset. In others, he captured graphic acts of auto-fellatio and self-penetration with sexual prostheses. No act was impossible when it could be realised through collage. Molinier is often depicted fucking himself through cut and paste, becoming the sole actor in a sexual coupling where he is at once male and female, active and passive. He told his biographer Pierre Petit that his multi-limbed figures were constructed to imitate pagan figures, Hindu gods and Masonic symbols in a rejection of a Christian tradition. He also maintained that his practice was for his sexual gratification alone, once reflecting: “I made a career out of indulging my personal freedom.”

Molinier never labelled his sexuality, though he did assert that his leg fetishism wasn’t related to the gendered body. He stated: “the pure sexuality of a woman or a man does not arouse me in the least; yet a beautiful leg, a calf will arouse me immeasurably…legs of a woman or a man arouse me equally.” The artist’s movement towards provocative photomontage eventually garnered the attention of Raymond Borde, who filmed the experimental documentary Molinier, screened privately in 1964 . In 1968, he starred in Jean-Pierre Bouyxou’s improved short film Satan Bouche un Coin, in which he appeared as Androdyne, a devilishly queer-coded figure who conducts an autoerotic performance piece. Molinier wrote to Emmanuelle Arsan and photographed her in 1964, continuing a fervid correspondence with her until his death. He also began meeting regularly with surrealist painters Clovis Trouille and Gerard Lattier, who shared the artist’s propensity for the sacrilegious. His paintings progressed in the vein of Gustave Moreau and Franz von Stuck – he reportedly mixed his own sperm with the colour pigments, ever dedicated to authenticating the persona of one ‘without morals’. However, his blasphemous 1965 painting Oh! … Marie, Mère de Dieu ended his relationship with Breton. Apparently, the notoriously homophobic Breton considered a hermaphrodite Christ being fellated and anally penetrated to be a step too far – he refused to exhibit the piece, deeming it irreverent and pornographic. Molinier was once again exiled from a community of artists and took to working in relative reclusion.

It’s this glorification of taboo-breaking that makes Molinier’s biography difficult to decipher. Some have described the artist as a queer radical; others, a misogynistic pervert. Molinier was 18 years old when his sister passed away. He once claimed that as her body lay in her coffin, he crept into the room and started masturbating: “Even in death she was beautiful. I shot sperm on her belly, her legs, and on her funereal dress which she had on her. She took the best part of me with her to the other side.” It has been suggested that his stories were perverse mythomania designed to fortify the shock value of his transgressive oeuvre. But it is established fact that he served a month in Prison du Fort du Hâ for assaulting his wife Andrea and firing a gun above his cousin’s head. Andrea divorced Molinier the following year.

In the 1970s, the artist worked on publications with Peter Gorsen and produced a series of transvestitism photography with the Swiss painter Luciano Castelli, and later with the Bordeaux artist Thierry Agullo. Molinier bequeathed his body to medical science in 1972, amused that those who would come to dissect him would discover his toenails immaculately painted red. Four years later, he committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth in front of a mirror, apparently creating a tableau for his death as he had done for his photography. (Molinier once confessed his three passions to be ‘painting, girls and guns’). He left a note on the door: ‘I’m killing myself, the key is with Claude Fonsale, the lawyer.’ Beside his corpse was a second note, railing against ‘all the bastards who have been a pain in the arse all my bloody life.’

Paul Clinton writes that Molinier’s depictions of himself ‘carry negative connotations of the transvestite, who fetishizes the feminine, reducing women to sexualized objects, or by associating womanliness with passivity.’ Certainly, Molinier’s obsession with self-gratification points to something more unsavoury than a strict desire to disrupt the heteronormative. What’s more, his murky biography speaks of a man whose narcissism compromised the safety of those closest to him. However, there is a radical vein of self-actualisation to glean from his work; that of gleeful queerness – a performance of the self that ridicules the conservative organisation of gender and sexuality. Molinier’s monochromatic vignettes thrusted the observer into the position of voyeur, forcing onlookers to reconcile with a gender identity and sexuality that cannot be neatly categorised. His work was exhibited at the 2013 Venice Biennale, and his pieces have come to inspire queer artists including Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Kat Toronto (aka Miss Meatface) and Ali Mahdavi.

Pierre Molinier is represented by Mennour.

References

Bernard, Sophie, ‘Pierre Molinier: The Body at Work”, Blind <Pierre Molinier: The Body at Work — Blind Magazine (blind-magazine.com)>

Clinton, Paul, ‘Pierre Molinier: ‘A man without morals”, Art Basel <Pierre Molinier: ‘A man without morals’ | Art Basel>

Conway, James J., ‘Molinier Family Values’, Strange Flowers <https://strangeflowers.wordpress.com/2010/03/03/molinier-family-values/>

Gallagher, Paul, ‘Sex, Death & Fishnets in the Surreal Film ‘Satan Bouche un Coin”, Dangerous Minds <https://dangerousminds.net/comments/sex_death_fishnets_in_the_surreal_film_satan_bouche_un_coin_nsfw>

Gorson, Peter, The Artists Desiring Gaze on Objects of Fetishism, in Pierre Molinier (Plug in Editions, 1995)

Here TV, The Legs of Saint Pierre (Les Jambes de Saint-Pierre), YouTube <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7KuWqil1y84>

‘Pierre Molinier’, Citizendium <https://en.citizendium.org/wiki/Pierre_Molinier>

‘Pierre Molinier’, Karsten Schubert London <https://www.karstenschubert.com/artists/99-pierre-molinier/>

‘Pierre Molinier’, Mennour <https://mennour.com/artists/pierre-molinier>

Searle, Adrian, ‘Pioneer of Perversity: Pierre Molinier’s extreme exposures’ The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/aug/25/pioneer-of-perversity-pierre-molinier-extreme-exposures>

Skidmore, Maisie, ‘The Forbidden Photo-Collages of Pierre Molinier’, AnOther Magazine <https://www.anothermag.com/art-photography/8019/the-forbidden-photo-collages-of-pierre-molinier>

Leave a comment