‘I’ve been in therapy since 18 months old, started drugs at 12, was diagnosed as schizophrenic at 19, started hormones the week after I quit Thorazine, got my dick inverted at 21, kicked heroin 6 years ago. Have been anorexic since 19 and plan to continue and you know what I say FUCK recovery, FUCK PSYCHIATRY, fuck it all because I’m over it. Over the roof. I’m so sick I’m dead, so from now on I take no responsibility for my actions. Oh, and I was fucked up the ass by my grandfather since age 5, been brutally raped twice and have had almost every major organ in my body fail at some point. Life support is no picnic for Rhoda so don’t EVEN take me there. By the way, I’m an artist and Andy Warhol was the dullest person I ever met in my life. But he’s got a museum so what do I know. Hans Bellmer is my favorite artist.

Love always,

Greer.’(Greer Lankton’s artist statement for It’s All About ME, Not You, 1996.)

Greer Lankton was an artist celebrated for her elaborate and often autobiographical dolls. She was born 21st April 1958 in Flint, Michigan, to Presbyterian parents. She was raised in Park Forest, Illinois, where she graduated a year early from high school to attend the Art Institute of Chicago from 1975 to 1978. From a young age, Lankton was preoccupied with becoming ‘pretty.’ In a 1984 interview, she said, “Ever since I was little, I wanted to be a girl. It was an art piece deciding who I was going to be, the process of making myself pretty.” As a toddler, she would put a washcloth on her head to mimic the long hair of her sister. She gravitated towards girls’ clothing and she loved to play with dolls. By Lankton’s reckoning, she was only 18 months old when her parents first took her to a psychiatrist – apparently an effort to correct behaviour they deemed unnatural in a child assigned male at birth. Stripped of her ‘girl’s toys,’ Lankton began crafting dolls from unconventional materials such as hollyhocks, flowers, and pipe cleaners. ‘My doll obsession manifest[ed] itself at a very young age,’ she wrote when she was eighteen. ‘Dolls became more important than friends… I feel my dolls in particular are very strong statements about ‘the human condition’; by mirroring our exteriors they capture our souls.’ By the time she was in sixth grade, Lankton’s materials became more sophisticated. She fashioned dolls from soda bottles and stuffing, built upon intricate skeletons assembled from wire hangers and umbrella shafts. Lankton once wrote, ‘If you think you have the wrong body, you’re always going to think about it.’

Lankton suffered numerous breakdowns and hospitalisations throughout her life. She claimed to have been sexually abused by her grandfather from the time she was five and felt her parents had failed to adequately protect her. At 19, she was assaulted at a bar, and subsequently attempted suicide. She struggled with anorexia and was diagnosed with schizophrenia, eventually replacing Thorazine with hormone injections to further feminise her appearance. It was while studying for her BMA at Pratt Institute at the age of 21 that Lankton underwent a difficult gender confirmation surgery, which contributed to a host of ongoing physical problems (she opted for a less reputable surgeon, Dr Richard Murray of Youngstown Hospital. She referred to his practice ‘the K-Mart of sex-change operations.’) Her boyfriend, Robert Vitale, rejected her shortly thereafter – an experience Nan Goldin described as ‘traumatic.’

Lankton’s stance on her transition remains unclear. She suggested that she felt rushed by her parents to undergo the surgery, claiming her father had convinced the church’s board to cover the cost of her operation. In a 2011 interview with Jame St. James, Lankton’s close friend, Van Barnes, recalled, “[Lankton’s] parents […] thought it was better for her – instead of living as a gay male, y’know, and how that would look probably on them – they wanted her to live as a woman.” Similarly, Goldin wrote, ‘[Lankton] often regretted her sex change, feeling she had been rushed into it at too early age and wished she had had the courage and support to live her life as a drag queen.’ The point is contentious, and a decision that Lankton appears to have been in constant flux with. Some of her dolls equate the trans experience with something akin to body horror. Hermaphrodite Giving Birth (1976), Battered Figure (1979), and Red Womb (1980) communicate embattled embodiment, and the pain of being viewed as ‘other.’ But the burden of sexed flesh is always ameliorated through self-decoration. By all accounts, Lankton loved glamour. As a teen, Peter Hujar’s Candy Darling on her Deathbed (1973) was plastered on her bedroom wall, and she devoured information about doomed socialites and tragic icons including Edie Sedgwick, Marilyn Monroe, and Greta Garbo. She highlighted her naturally blonde hair to a vivid gold, perfumed herself with a mix of Kiehl’s Chinese Flowers and Chanel N°5, and painted her face with red Chanel lipstick and Shiseido powder. Later in life, Lankton stated, “I don’t really feel like either sex, but I think I look more like a girl than a boy.” She also wrote positively of her transition as a process of self-actualisation: ‘This has hit so hard I can’t stop crying. Finally I too can be human.’

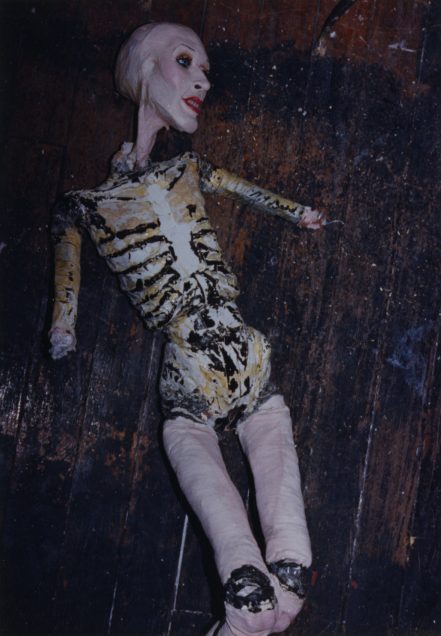

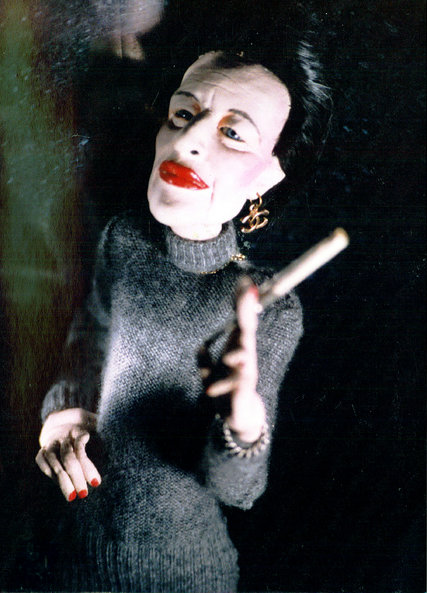

In 1979, Lankton began working on Sissy (1979-1996) while recovering from her vaginoplasty. Like her creator, Sissy stood at five-foot-eight and weighed 110 pounds – a somewhat abject figure with hollowed out cheeks and gamine features. Up until Lankton’s death, her dolls went through a series of what that artist termed ‘operations.’ Dolls lost weight, gained weight, were dismembered and remodelled. Archival photographs show Sissy attenuated, disassembled – her expression and genitalia continually altered and rebuilt. She is at once glamorous and grotesque, somewhere between Egon Schiele’s subjects, Hans Bellmer’s poupées, and Lester Gaba’s untouchable ‘Gaba Girls.’ Sometimes Sissy is stripped of accoutrements; at other times, she is adorned with elaborate clothes, wigs and cosmetics – embodiment made bearable through ornamentation. Like Lankton, Sissy resists any fixed essentialism – she is uncertain, fluid, and ever-evolving. Where many viewed her creations as disturbing, Lankton considered her dolls fashionable and friendly; “the kind of people you’d like to know about. Really interesting and fucked-up.”

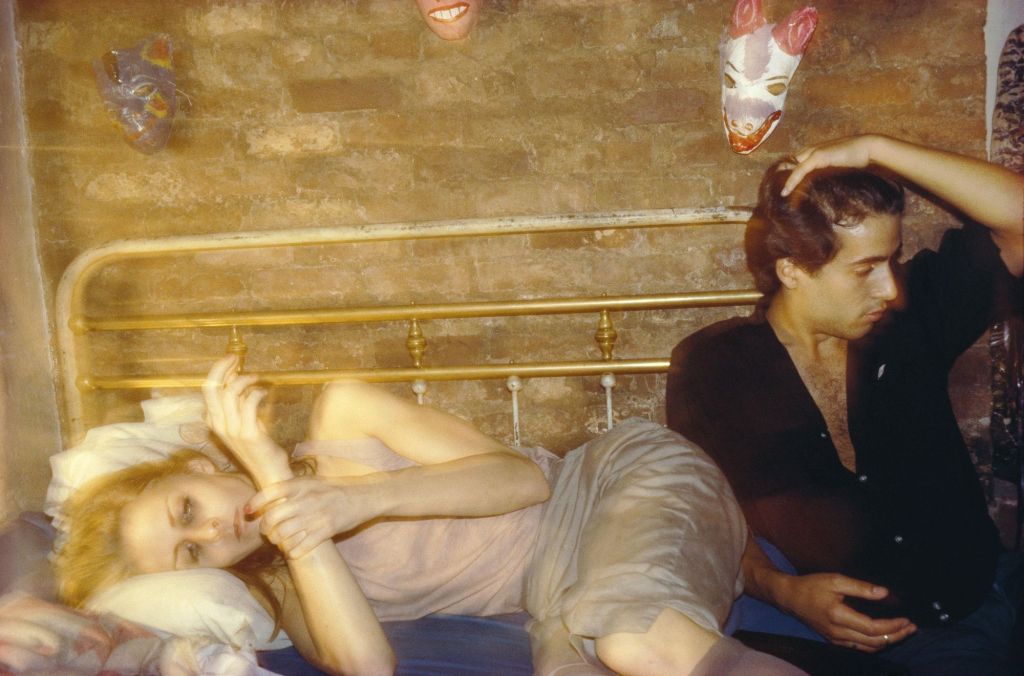

After graduating from Pratt Institute in 1981, Lankton moved to New York. It was here that she met some of the most significant artists in New York City’s East Village. She collaborated with and inspired fellow artists including David Wojanrowicz and Nick Zedd. She lived with Nan Goldin in the Bowery, who photographed Lankton extensively. That year, Diego Cortez included Lankton’s work in the seminal ‘New York / New Wave’ exhibition at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center (now MoMA PS1), which also featured such luminaries as Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Robert Mapplethorpe. Here, she garnered the attention of Dean Savard, who awarded Lankton her first solo show at his gallery, Civilian Warfare, in 1983. The queer photographer, Peter Hujar, photographed Lankton for the show’s promotional posters – she appears nude, reclining alongside the frail Sissy and the zaftig Princess Pamela (1980-1983). The latter reportedly started life as Madame Eadie, a ‘fat suit’ Lankton assembled and donned at parties. She would later rebuild the suit into Dee Dee Lux (appearing as Lux in Nick Zedd’s The Bogus Man), before crafting the final incarnation in the image of African American chef and jazz singer, Pamela Stroebel. Pamela appears in stark contrast to Sissy – pneumatic, vibrant, carefree. Karen Karuza recalls that Lankton, “was the most confident and magnetic person in the room” when she was dressed as Eadie. Through Lankton’s art we see freedom in the fat body – a defiance she struggled to embrace as she worked for ‘passable’ prettiness.

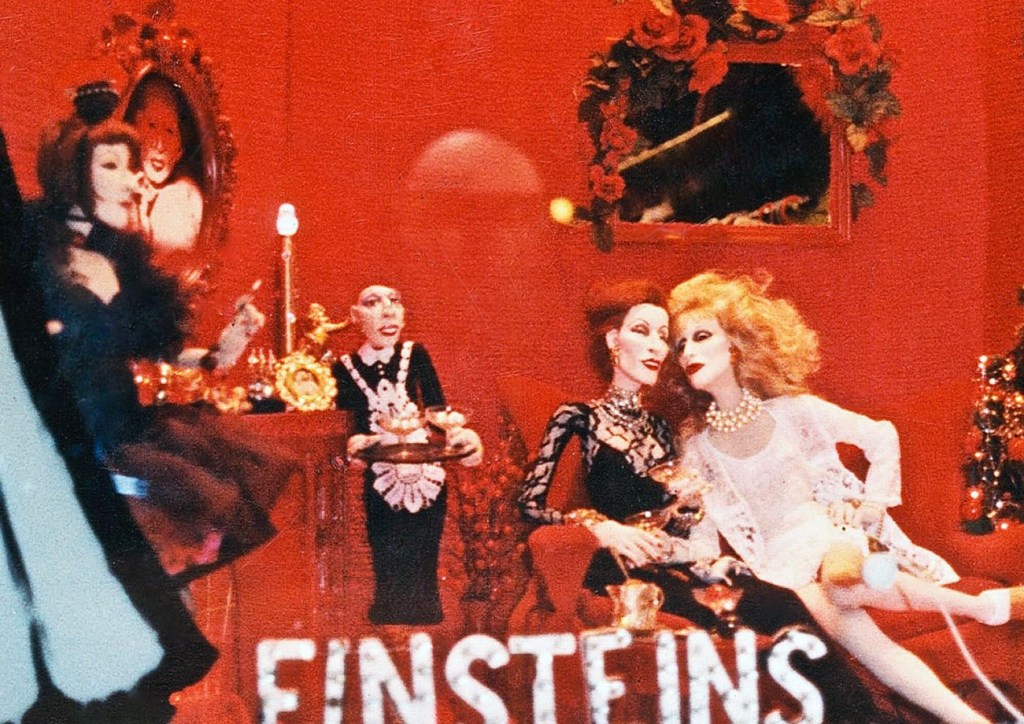

In 1982, Lankton began dating clothing and jewellery store owner, Paul Monroe. The window of Monroe’s East 7th Street boutique Einsteins became infamous for Lankton’s dolls placed in elaborate tableaux vivants. The displays were populated with effigies of muses and misfits from high and low culture, from Divine and Teri Toye, to Jackie Onassis and Coco Chanel. Lankton’s displays were reportedly admired by Diana Vreeland, and Andy Warhol and Iggy Pop were amongst those who frequented the store. “Greer adored celebrity,” Monroe remembers. “Every Monday she would race to the newsstand to get the latest copies of Star, People, and any other trashy gossip rag […] but she had to be deeply infatuated with the person; it wasn’t based on what or who would be most popular.” Lankton evidently revered the radicalism of countercultural celebrities, as well as mainstream stars who battled significant personal adversity. Their cachet within queer culture speaks to the artist’s love and admiration for her community.

Monroe and Lankton married in 1987, on the fifth anniversary of their first date. Lankton’s father acted as minister, Teri Toye the maid-of-honour, Peter Hujar the best man, and Nan Goldin the wedding photographer. Goldin’s pictures show Lankton grinning radiantly in her grandmother’s reconstructed wedding dress – the image of near-traditional matrimony, offset by Winston Lights and Monroe’s lime green hair. Lankton continued to showcase her work at Civilian Warfare (with solo shows in 1984 and 1985), P.S. 1, the Gracie Mansion Gallery, and many other local galleries during her marriage. In 1985, she even feathered Big Bird for the Sesame Street film, Follow That Bird.

Like many of New York’s downtown creatives, Lankton was a regular fixture at Pyramid Club, Area and Mudd Club. Eventually, her use of she synthetic drug MDA graduated to cocaine, and she began using heroin regularly. Her health continued to suffer, her severe asthma likely exacerbated by her growing drug dependence and dwindling weight. Her 1988 daily planner captures a series of psychotic episodes, seizures, detoxifications, and relapses (‘Doing Heroin AGAIN’). For extra cash, Greer worked as a studio assistant for other artists including puppet-maker Kermit Love (The Muppets, Sesame Street). She kept obsessive inventories of money spent and money owed, and meticulous plans for her gallery, The Doll Club. ‘I feel lost, without direction or purpose,’ she wrote. ‘Next to Paul I feel so lazy and slow. I’m trying to gain weight but as usual am filled with panic.’

By this time, Lankton had lost numerous friends, ex-lovers and contemporaries to the AIDs epidemic, including Max Dicorcia, Peter Hujar, Robert Vitale, and Ethel Eichelberger. In 1989, she contributed to Nan Goldin’s exhibition Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing at Artists Space, New York – a response to AIDS related deaths amongst the East Village queer community. Lankton hung dolls’ skins on the wall and wrote in the exhibition catalogue: ‘Having watched so many friends die from AIDS has been like surgery without anaesthesia. I have found it very difficult to relate my emotional responses to my art work. It seems like nothing I could make would adequately describe the grief I feel. The skins I have made are just mementos, like the skin we wear when we are alive becomes just a memento after we die.’

Eventually, her marriage grew caustic. In September 1990, Monroe was arrested for allegedly assaulting his wife, and the mounting difficulties impacted Lankton’s career. She was commissioned to produce 15 dolls for Barneys’ Christmas window display for a total of $30,000, and though she completed dolls of Anna Wintour and Diana Vreeland, Lankton’s contract was eventually terminated. (Barneys cited Lankton’s apparent failure to produce ‘adequate assurances’ as to the project’s progression – and ‘the content and tone’ of their telephone conversations with Monroe – as a cause for concern. Lankton was later threatened with legal action.) Lankton and Monroe separated around this time. Julia Morton remembers the pair as ‘abusive drug addicts,’ and claims they finalised their divorce in 1993. Monroe insists that they were never formally divorced, arguing that Lankton’s mother forged the papers. He still remembers Lankton fondly: “Greer was an angel, my angel […] I couldn’t resist her charm, her beauty, and her god-given skill.”

Lankton moved back to Chicago in 1991. She became acquainted with local club kids including Joey Arias and her apprentice, JoJo Baby, and seems to have maintained a full if somewhat chaotic social life. She entered the South Suburban Council on Alcoholism and Substance Abuse to detox from heroin, which she subsequently sublimated with alcohol, cocaine and codeine (a sloppily penned journal entry from May 1991 reads: ‘Why can’t I just be straight? It’s depression. I’m lonely for love, very lonely for it. I miss Paul. I miss all my dead friends’). She moved into a studio apartment in Morris, Illinois, and briefly worked at the punk store The Alley, where she dressed the windows with her dolls. She eventually found herself living on welfare and food stamps as her health further declined, but she continued to make money from her dolls. Iggy Pop and Anna Sui were amongst her more notable buyers. In August 1991, Greer slit her wrists – a week after her friend David Wojnarowicz lost his battle with the AIDS virus.

In 1994, curator Klaus Kertess went to Chicago to select artists for the March – June 1995 Whitney Biennial. Kertess described visiting an ‘emaciated’ Lankton ‘in her claustrophobic apartment and looking back and forth between this intense male doll — the only male doll in the apartment and somehow the most pathos-ridden — and Greer, in an animal-print dress that made her look like the doll.’ Four of Lankton’s pieces were featured in the exhibit – alongside the work of Todd Haynes, Cindy Sherman and Jim Jarmusch – and were subsequently included in the Venice Biennial that same year. In a review of the Whitney exhibit, The New York Times described Lankton’s creations as: ‘a meld of Egon Schiele and Hans Bellmer, though they can be surprisingly funny.’ In 1996, Lankton was also included in University of Minnesota’s Heterogeneous exhibition. The surge in coverage attracted the attention of Margery King, curator of the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, who invited Lankton to create a replica of her apartment for a show at the Mattress Factory.

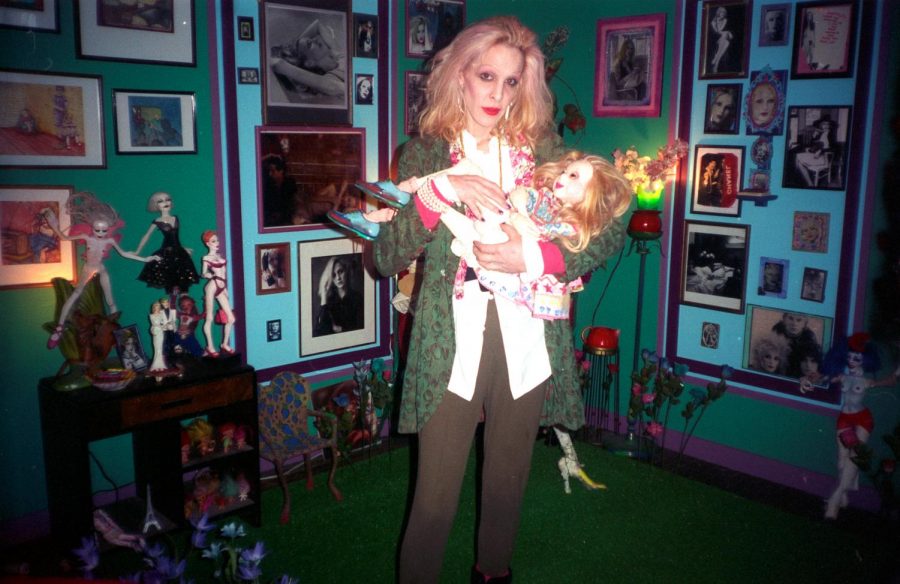

Lankton worked tirelessly on the show for almost a year. During this time, she was reportedly raped in an alley behind her apartment building and developed Toxic shock syndrome (she later recounted the ordeal to a photographer of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette). Lankton refused to take time off to recover, insisting that she had to complete her work for the exhibit. In October 1996, she recreated her Chicago apartment in the Mattress Factory, building a freestanding ‘white trash’ house with a gate surrounded by an Astroturf patio. Ruby slippers and striped stockinged feet emerged from the threshold, inviting visitors into Lankton’s technicolour world. Inside, fantasy and reality collided, the space wall-to-wall with tchotchkes and pathos-ridden pieces addressing heroin abuse, the AIDS crisis, body dysmorphia and suicidality in a confrontational blend of innocence, hope, degradation and despair. Personal shrines to Patti Smith, Candy Darling, Jesus, and to Lankton herself decorated the walls – a veneration of those who dared to be singularly themselves. The space was punctuated with dolls Greer created throughout her life; most notably, an anorexic bust named More Morphine (1990-1996), deteriorating in a bed prophetically strewn with pill bottles. Lankton wore her cut up and reconstructed wedding dress to the opening of the exhibition.

Lankton named her installation It’s All About ME, Not You. Though her work was personal in nature, the title playfully underscores a certain egoism in memoir, as well as the tireless reduction of queer art to unbending autobiography. This is further evidenced in a poem Lankton wrote for the show’s press release:

Artificial Nature

Total Indulgence

Dolls engrossed in glamour and self abuse

The vanity

The junkie

The anorexic

The chronic masturbator

“Its all about ME”

Not you

Trapped in my own world in my

H \ head in my tiny tiny

apartment

As William J. Simmons writes, ‘[Lankton’s] final exhibition is about herself and not about herself. It is about herself and the discourse surrounding herself’ – or rather, the discourse surrounding herself and queerness more broadly. Lankton understood the derogatory stereotypes attributed to herself and those within her community who were so often represented as drug addicts, narcissists and sexual deviants supposedly complicit in their victimisation, as well as society’s lurid fascination with the queer body. This had become especially egregious in the objectification and othering of HIV positive people, with mass media representing queer sexuality as a kind of disease borne from immoral and deviant behaviour. Through depictions of queer trauma and self-abuse, Lankton exposed the violence of the cis-hetero gaze that brutalises, pathologizes and dissects queer and non-normatively gendered people. Where exclusionary discourse rejects the trans body as not ‘real’ and thus ‘invalid,’ Greer reclaimed ‘artificiality’ as a process of self-determination – what Judith Butler famously described as the creation of a ‘liveable life’ within the restrictions of the cis-hetero binary. “I will not die,” Greer wrote in her 1977 journal, shortly before deciding to transition. “I will become.”

As with so many trans lives, Lankton’s time was tragically cut short. She passed on 18th November 1996 from an overdose of cocaine, just a month after the debut of her installation. She was 38. Lankton’s father conducted her memorial service. Her obituary was written by Nan Goldin and published in The New York Times. Lankton’s mother told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “Greer had always been a different child. I had concerns when she was 2.”

Some of Greer’s work has been lost to time, while the rest is held by various individuals and institutions including MoMA. Lankton’s narrative is so complex that even in death, any agreed determination of her legacy seems unlikely. Some claim her overdose was intentional; others argue it was accidental. The Mattress Factory now own a large portion of the artist’s work and personal affects as bequeathed by the Lankton family. The gallery’s archivists continue to digitise thousands of items including Greer’s photographs, journals, paintings and personal correspondence. Paul Monroe, on the other hand, claims Greer’s family threw their daughter’s artwork into a dumpster shortly after her death – a version of events that was corroborated by JoJo Baby. Monroe continues to build up the Greer Lankton Archives Museum (GLAM) to honour his ex-partner’s life and career. “I realized I had over 3,000 negatives, piles of photos, and around 30 pieces of Greer’s work,” he told LACMA’s Rita Gonzalez. “I decided to hunt for whatever I could find that she made. I started going through old records and receipts of work she sold through Einsteins and from her gallery The Doll Club.”

Monroe has developed plans for a documentary that will bring Lankton’s life and work to screen. His close friend and occasional roommate, Lena Dunham, is said to be producing the film. In recent years, interest in Lankton’s work has revived, with exhibits including Participant Inc.’s Greer Lankton: Love Me (2014), and Company Gallery’s Doll Party (2022). Her work was also featured in LACMA’s presentation, Outliers and American Vanguard Art (2018-2019). It’s All About ME, Not You is now one of the Mattress Factory’s permanent installations.

A walkthrough of It’s All About ME, Not You and selections from Lankton’s archive can be viewed on YouTube.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply